On 9 December 2025, Dr Gaiane Nuridzhanian, Associate Professor and Leader of the Research Group for Human Rights and International Law at UiT Faculty of Law, participated in Oslo Peace Days 2025.

Nyhetsarkiv

16.12.2025:

– Avgjerande for Ukrainas framtid

Sikkerhet og økonomi kjem til å spele ei viktig rolle i gjenoppbygginga av Ukraina. Ein annan viktig berebjelke er dessutan rettstryggleik og rettferd. På dette området kan UiT gi eit viktig bidrag.

10.12.2025:

Et viktig steg for ansvarliggjøring

FNs verdenserklæring om menneskerettigheter markeres 10. desember. I en tid preget av krig i Europa belyser menneskerettighetsekspert Nuridzhanian omfanget av menneskerettighetsbrudd i krigen i Ukraina og hvordan den nyopprettede spesialdomstolen for aggresjonsforbrytelser kan gi rettferdighet.

08.12.2025:

Seminar on Developments in the Law of State Immunity

On 20 November 2025 the research group for Human Rights and International Law at UiT organized an all-day seminar on ‘Developments In the Law of State Immunity’. Researchers from European institutions met in Tromsø to present and discuss their research on a hotly debated topic of international law.

21.10.2025:

Møte i San Remo

Oppdatering av San Remo manualen om folkerett for væpnede konflikter til sjøs.

20.10.2025:

Til Wien som gjesteforsker

Hannah Bekkelund er på sitt andre år som stipendiat i rettsvitenskap ved Det juridiske fakultet, UiT. For ikke så lang tid tilbake returnerte hun til Tromsø etter å ha vært på et lengre gjesteforskeropphold i utlandet. Hennes faglige fordypningsområde, EØS-rett og menneskerettigheter, førte henne til Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Fundamental and Human Rights i Wien.

24.09.2025:

Folkerettens rolle i uroens tid

Folkeretten er under stadig økende press i vår tid hvor krig og geopolitiske spenninger skaper utrygghet i verden. Kan vi fortsatt se til folkeretten når stater går til angrep på andre stater, eller når en stat begår folkemord? Kan vi forvente at folkeretten fremover vil ha effektivitet og kan spille en sentral rolle i opprettholdelsen av fred og stabilitet gjennom internasjonalt samarbeid?

28.08.2025:

Seminar on the Role of Law in Peacemaking with Professor Sarah Nouwen

The Faculty of Law at UiT – The Arctic University of Norway – recently had the pleasure of hosting a seminar with Professor Sarah Nouwen on the development of a legal framework for peacemaking.

24.03.2025:

No lasting peace without justice

Members of the Human Rights and International Law Research Group discuss the role of justice in achieving lasting peace in Ukraine.

27.02.2025:

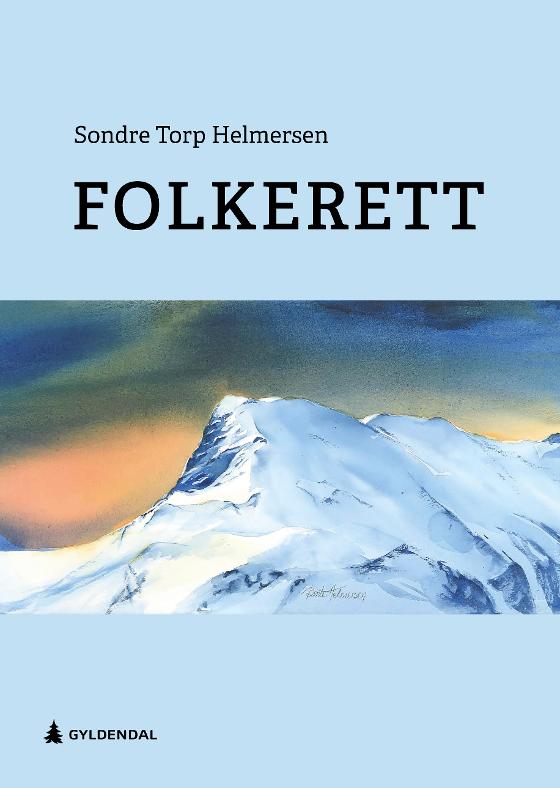

Ny lærebok om folkeretten

Professor i rettsvitenskap Sondre Torp Helmersen har nylig utgitt en oppdatert og utvidet lærerbok om den alminnelige folkeretten.

31.10.2024:

Workshop on Law and Disinformation

On 24 October 2024, the FAKENEWS project at UiT, in cooperation with the Constitutional Law Research Group at the UiT Faculty of Law, hosted a workshop on Law and Disinformation.

15.08.2024:

One Crime, One Punishment: A Deep Dive Into ‘Ne Bis in Idem’ in International Criminal Law

Associate Professor Gaiane Nuridzhanian delves into the intricate legal principle of ne bis in idem in recently published book.

28.02.2024:

Ukrainakrigen under lupen

Russiske krigsforbrytelser, kulturell motstand og geopolitiske implikasjoner.

22.01.2024:

Forskergruppa for statsrett har fått ny leder

Sondre Torp Helmersen tar over stafettpinnen som ny forskergruppeleder.

19.01.2024:

Ti år siden Russlands invasjon av Ukraina

Konferanse på UiT om krigens konsekvenser for ukrainere og den geopolitiske situasjonen.

18.01.2024:

Ti år siden Russlands invasjon av Ukraina - Heldagskonferanse på UiT 22. februar

Den 22. februar avholdes det en heldagskonferanse på UiT for å markere tiårsdagen for Russlands invasjon av Ukraina. Konferansen tar også for seg de to siste årene, hvor Russland har ført en fullskala krig mot Ukraina.

22.04.2022:

Naval Warfare and the Law of the Sea - workshop

Det juridiske fakultet arrangerer den tverrfaglige workshopen «Naval Warfare and the Law of the Sea» tirsdag 3. og onsdag 4. mai.

27.01.2022:

Magne Frostad er ny leder i forskergruppa for statsrett

Frostad er professor ved det juridiske fakultet og har statsrett og folkerett som sine spesifalfelt. Særlig reglene om når stater kan bruke militær makt (jus ad bellum) og hvilke regler som gjelder når de gjør dette (jus in bello), samt menneskerettigheter og havrett.

12.10.2021:

Hvilken betydning har folkerettslitteraturen for avgjørelsene til den internasjonale domstolen (ICJ)?

En førsteamanuensis ved UiT har lest 1200 ICJ-dommer for å finne svaret.